|

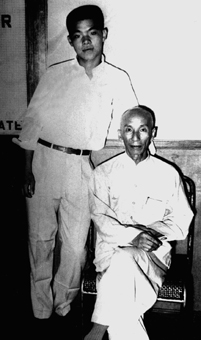

Part IV In Japan, the word "master" refers to any martial artist whose knowledge, skill and successes in a fighting art have been rewarded by advancement to the rank of fifth degree black belt. In China, a "master" earns that title through years of dedication as an instructor, through the credibility gained from a large following of students - especially those who have won championships of one kind of another - and through widespread acclamation by respected leaders in the martial arts community. In the West, however, the concept inflates to mythic proportions. A "master" of the martial arts here must possess the prowess of a professional fighter, the insight of an athletic coach, the mysticism of a guru, and an element of wizardry besides. Nothing less is acceptable. among the elite few, whose stature of martial arts excellence actualizes all three of these definitions, stands William Cheung. As one of the original instructors under the late Yip Man, wing chun's patriarch, no one involved with the art today could hold an official rank higher than Cheung's. He was Yips personal and most favoured student. He spent some seven gruelling years under the grandmaster's close scrutiny to acquire his present knowledge of wing chun. During this period, he established the wing chun clan's record for the most consecutive sticky-hand (chi sao) matches without a loss, destroying 32 opponents in less than one and a half hours. Also, he helped persuade Yip Man to reveal what has become wing chun's most famous training aid: the wooden dummy. The first wooden dummy in Hong Kong was built by cheung and his two brothers in the basement of their boyhood home. Also, while not yet an adolescent, he was responsible for starting his best friend, a younger boy named Bruce Lee, in kung fu lessons with Yip Man. As one of Yip's assistants, Cheung, along with Wong Shun Leung, actually became the now-famous Bruce Lee's primary sparring partner and instructor. By the time Cheung reached his middle teens, he had developed a reputation throughout Hong Kong as a streetfighter. He, Wong Shun Leung, and sometimes Bruce Lee, would represent the wing chun system in challenge matches fought on rooftops and in the streets against martial artists from other styles. Hong Kong's present-day rivalry between the wing chun and the choy li fut schools began at one of these challenge matches. As the years passed, Cheung's street confrontations became more frequent and more dangerous. Like the fastest gun in a Hollywood Western, the more challenges he won, the more of a target he became to adversaries. Rival martial artists and street gang members were seemingly always anxious to avenge the loss of face dealt to a defeated comrade by Cheung. they sent stronger and stronger champions to face him. Soon Cheung had begun to humiliate established martial arts instructors who had large followings. Then disaster struck. One of Cheung's opponents, a member of a powerful gang, lost an eye during their challenge match. cheung's enemies reacted gravely. A vendetta was proclaimed. Cheung found himself being ambushed by groups of young toughs wherever he went in the Crown Colony. Sometimes they came armed with knives, clubs, and various kung fu weaponry. Bruce Lee was awed by Cheung's ability to escape unscathed from such desperate circumstances. Many of Lee's students report, in fact, that throughout his life, Cheung served as Lee's mental image of the deadliest streetfighter alive, and the highest standard of wing chun combat skill. In 1959, William Cheung joined his older brothers in Australia in part to free himself from his own reputation. He arrived in the foreign nation with less than a high school education, and little knowledge of English. Yet, so determined was he to reverse the destructive direction of his life that, within a few years, he had graduated with a university degree in economics and mathematics.

His skill as an instructor has been proven by his students many times over the past several years. Most recently, two of Cheung's students attended the World Kung Fu Championships held in Hong Kong last November 21. This tournament, sponsored by the Hong Kong Chinese Martial Arts Association, ranks among the most prestigious martial arts events in Asia and is certainly the most prestigious in Hong Kong. Both of Cheung's students effortlessly pounded their way through divisional eliminations, using three-round full-contact rules, to win world championships. At the same time, William Cheung can at a moment's notice, summon all the mysterious qualities usually found only in martial arts legend. For example, during his first trip to the U.S., he astounded martial arts journalists not only with his uncommonly youthful appearance, but also with his apparent ability to make the length of his arm expand an extra inch upon command, his ability to extinguish a lighted cigarette on his tongue without pain, and his ability to stand on raw eggs without breaking them. He subsequently performed the latter feat, standing on only two eggs, before the cameras of TV's You Asked For It. Then, too, he possesses sufficient powers of concentration to offer substantial challenge in his weekly chess games with Guy West, Australia's third-ranked tournament chess master. Over

the past several months, William Cheung has

acted as a bard, almost in the Homeric tradition,

guiding readers through the epic experiences

of his friend Bruce Lee, of his teacher Yip

Man, and of his art's ancestral masters. This

final instalment of "The William Cheung

Story" tells hos Cheung himself became

involved with wing chun, and how that involvement

led to the revelation of a secret which forever

changed his life. "Challenge matches!"' Cheung Cheuk Hing whispered to himself, shaking his head, as he continued to muscle his way aggressively down the sidewalks of Kowloon's Junction Street. He quickly maneuvered past irritating produce vendors and shoved openings between slower pedestrians. The boy's rude behavior was unlike him. Instead of the usual beaming smile and relaxed bearing, familiar passers-by were met with an enraged glare and the demeanor of a startled lion. Cheuk Hing darted across the street without warning. A taxi screeched to a halt and blared its horn. Disaster was averted. Narrowly. The boy was deeply troubled. He did not know whether he should flare up in anger, or cry. His one thought was that he had to see his master, Yip Man. Only Yip Man might be able to help him. He boarded a bus headed for Lei Dat Street in the Yaumatei district of Kowloon. Like most public places in Hong Kong, the bus was filled to capacity, then beyond. There were no seats vacant, so the boy had to settle for standing in the aisle. Challenge matches, he thought. Challenge matches were so much a part of his life. Everything good and everything bad that happened to him seemed to center around challenge matches. Why, even his own first encounter with Yip Man had been at a challenge match. Ah Hing (as Cheung was called by his closest friends) had been 11 at the time. All of his matches in those days were confined to playground scuffles. Most of his athletic pursuits were as a member of his grammar school swim team. One of Ah Hing's tearn members had an older brother named Wong Shun Leung. At 17 years of age, Wong Shun Leung was tall, with a lean muscular frame and exceptional physical abilities. He also had an arrogant daredevil personality coupled with some basic knowledge of Western boxing and the sincere belief that no kung fu stylist in Hong Kong could hurt him. He frequently offered and accepted formal challenge matches from the local martial arts community. No one had beaten him. In fact, he had developed a lot of neighborhood fame for the ease with which he had disposed of a few self-proclaimed "masters." Ah Hing himself felt a great deal of admiration for Wong's pugilistic accomplishments, and for the esteem which they brought. Then one day during swimming practice, Wong's brother told Ah Hing that Wong Shun Leung had challenged some old man who claimed to know, of all things, a "woman's" style of kung fu. However, despite the silly origin of the old man's style, he was supposed to be quite proficient. On the day of the challenge match, Ah Hing and Wong's brother tagged along behind Wong Shun Leung to cheer him on. Wong led them to a small room inside the Restaurant Worker's Union Hall. The room could not have been larger than ten by 15 feet, smaller than a boxing ring. The boys were introduced to a short man in his mid-50s. He was dressed in traditional Chinese garb and could not have weighed more than 120 pounds. A bout with Wong Shun Leung seemed unfair. Wong was much too big for him. Yet the old man's face radiated a broad, friendly smile. He thought the idea that three kids would come to challenge him to be very funny, and he was anxious to get started. The hallway outside the room quickly filled with spectators, their heads bobbing from side to side like pendulums, each trying to catch a better glimpse of the spectacle. Wong got the match under way by bouncing aggressively toward the old man, jabbing as he went. A moment later, Wong's body thudded against the floor. The old man had thrown him-neither Wong nor the spectators had seen how it was accomplished. Wong scampered to his feet, confused but valiant. He attacked again. The old man's hands moved with the same blinding speed as he sidestepped the attack. Wong was on the floor once more. Wong Shun Leung got to his feet and paused for a moment to take a deep breath. He stared intently at the old man. Then, mustering all of his youthful vigor, he made a powerful kamikaze dive for the old man. But this time the man seemed to bring his hands up from underneath somehow, lifting Wong into the air, and ... THUD-D! Wong landed heavily on his back side. The challenge match was over. That incident had occurred almost three years ago. The bus stopped and one of the seated passengers got off. Ah Hing quickly sat down in his place. Ah Hing smiled briefly as he remembered that after the challenge match Wong had vowed that, eventually, he would go back and beat up the old man. Yet secretly he had doubled back that same day and asked the old man to accept him as a student. Several months passed. Wong maintained his insistence that ultimately revenge would be his against the old man. But at Wong's next challenge match, instead of assuming the stance of a Western boxer, he stood in a posture which looked curiously reminiscent of the old man's. In the ensuing challenge match, Ah Hing and his two older brothers witnessed a brand new Wong Shun Leung. They marveled at how awesome Wong's fighting prowess had become in such a short time. He no longer bounced on his feet, looking for openings, and absorbing a blow or two as he moved in. Now he jammed kicks and punches, and rendered his opponent helpless with a rapid-fire burst of straight punches to the head. The Cheung brothers decided that Wong had the right idea. They too should learn from the old man rather than try to beat him up for the sake of neighborhood honor. They soon came to know, of course, that the old man's name was Yip Man. He was the grandmaster of a style of kung fu called wing chun. The bus finally reached Lei Dat Street, and Ah Hing got off. He resumed his determined pace as he walked steadily toward Yip Man's studio. He desperately needed to talk to his teacher. Ah Hing had always felt a kinship with Yip Man, even in the beginning when he took lessons in the same class with his two brothers. Tsui Sung Ting would usually conduct the class and Yip Man would watch from the back of the room. Invariably, Yip would personally come and correct Ah Hing's movements. No one eise's. Just Ah Hing's. Then with an affectionate wink of an eye, he'd return to the back of the room. After class Yip might start up a conversation with the boy, or possibly tell him a joke or two. They quickly developed a close relationship. Within a year, Ah Hing had earned his own reputation as a competent fighter among the kids on the school playground, and with members of the local neighborhood gangs. At the age of 12, he accepted his first formal challenge match. He was big for his age, so he drew a fully grown tai chi chuan expert. The man was quite fat, however. Ah Hing needed but one punch to the belly to send the man fleeing for safety. Other challenge matches followed. Ah Hing liked the respect he gained with rivals and the hero worship he gleaned with friends from each victory. But now, two years later, his challenge matches had become a source of personal pain and insecurity. Ah Hing burst into Yip Man's studio like a fawn escaping the flames of a forest fire. "Sifu! Sifu!' he cried. Ah Hing knew that Yip Man did not like to be disturbed so abruptly, especially during his rest period before the day's classes began. Yip considered such insistent conduct, which characterized most of his youthful kung fu students, to be rude and unworthy. The master usually rewarded their bad manners by offering them little or no personal attention. "Sifu!" Ah Hing cried again, risking the old man's wrath. Yip Man emerged quietly from his living quarters in back of the studio. His deeply chiseled facial features registered concern. "Ah Hing," he said. "By the gods, what could cause you to make so much noise?" "Sifu, may I come live with you?" the boy blurted out. Yip Man did not answer. So startling a request had dumbfounded him. "I-I can't take it anymore," Ah Hing continued. "Every time I get into a fight or accept a challenge match ... it doesn't matter whether I'm in the right or not ... I get in trouble at home. My father is always riding me about it. And now the police are involved, again! "I can't go home, Sifu. I'd lose too much face if I couldn't defend my honor or protect my friends." Yip Man studied the boy's face. The old master had had many fights of his own as a youth, so he knew well that they could become almost a life-or-death obsession for a teenage boy in Hong Kong. The city was overpopulated to an extreme, and poverty was everywhere. Most teenagers dropped out of school after the sixth grade because the Crown Colony government was unwilling to subsidize their education further. Jobs were scarce. And so, left idle by society, thousands of bored youths would band together into gangs and scour local neighborhoods, looking for excitement. Clash was inevitable. Fighting, therefore, frequently became as much of a national pastime for a boy growing up in Hong Kong as soccer. And more. To many, a streetwise sense of honor and pugilistic skill were the only available measures of self-worth. But Ah Hing had a different problem. His father was a high-ranking police inspector. And since the boy was a very good fighter, his fights sometimes brought police intervention. These incidents embarrassed his father. Besides, his father could not see how fighting could prepare him to earn a living as an adult. Yip Man remembered that shortly after Ah Hing began accepting challenge matches, the boy's father had cut off his allowance so that he could no longer afford kung fu lessons. But the boy exhibited so much talent and dedication that Yip Man allowed him to continue, tuition free, on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays-the days his two older brothers did not come to class. "What would your family say," Yip Man asked. "Sifu," the boy answered slowly, fighting back tears. "My father does not want me." Yip Man thought for a moment. Perhaps some good could come of this. Certainly it would give him a chance to watch his disciple a little more closely, to become more sure of him. Yip smiled. "Okay, Ah Hing. You can stay." "Really? I promise, you won't be sorry. I'll do all the house chores. I'll wash the dishes, I'll do the laundry, I'll . . ." "You don't have to do all that. There's nothing grand about this. Just come and stay. You'll sleep on a cot in the corridor. And when my wife cooks, you'll eat what I eat. When it comes time to practice, you'll practice. That's all." Within a few weeks Ah Hing had become installed, along with Leung Sheung, Lok Yiu, Tsui Sung Ting and Wong Shun Leung, as one of the grandmaster's assistant instructors. He would help out the other instructors with the regular group lessons, and he would usually accompany Yip Man each afternoon to the private lessons his master gave to the rich clients. Yip Man was very impatient with these private students because he did not like to teach beginners. So to minimize his own frustration, he would demonstrate the new techniques one time, then sit down and observe while Ah Hing completed the lesson. For Ah Hing's part, he loved this new relationship. It afforded him the opportunity to spend as many hours a day as he wished, sharpening his own wing chun skills under the corrective eyes of the great teacher. Of course Ah Hing continued to accept challenge matches. Many of these matches were arranged by Wong Kue, a southern praying-mantis stylist who once had been beaten by Wong Shun Leung. After his defeat, he became driven with the need to uncover the "golden truth" about the relative battle effectiveness of noted martial artists and notorious streetfighters. He arranged for literally dozens of such match-ups. The rules for a challenge match were uncomplicated: no poking the eyes, and no "frying the chestnuts" (grabbing the groin). Everything else was legal. However, many matches ended ambiguously since one of the challengers would run away, claiming that he had won through the use of the dim mak death touch. His opponent would surely drop dead within a few days or weeks. By the time Cheung Cheuk Hing had reached his 14th birthday, he had been death-touched at least as many times. Yet, despite the frequency of his demise, the boy was astonished at how well he could continue to do the simple things, like eat, sleep, breathe ... and fight! The months passed easily with Yip Man. And Ah Hing found his kung fu skills growing steadily stronger. Then late one night, about six months after he had first come to live with Yip, the old man approached him as he prepared for bed. "Ah Hing," his master had said. "it's now time. I want you to get dressed and cleaned up. Then come meet me inside at the ancestral shrine." When the boy had done as he was told, Yip Man instructed him to kneel down beside him in front of the shrine. Ah Hing had never before seen Yip act so solemn, nor speak so sternly. "Ah Hing, you must now take a vow," began Yip. "And you must consider this vow sacred. In fact, this may be the most important vow you have ever taken because it will test the very fabric of your honor. "You must swear this vow to each of the ancestral masters of the wing chun clan, and to each of their subsequent descendants, beginning with the elders of the Shaolin Temple and ending with me. "Ah Hing, you must swear that what I teach you in private ... shall remain private. Now let us begin." The vow ceremony lasted for about an hour. Afterward, Yip Man sent the boy to bed with one final reminder, "From now on, Ah Hing, when I teach you a technique that I say is secret, then, by the gods, you are not to teach it to anyone. The knowledge is mine. When I die the knowledge becomes yours. Until then, I decide who shall learn. Do you understand?" "Yes, teacher," the boy answered simply. Ah Hing had trouble sleeping that night. He was too excited, too filled with questions. He wanted to know what his instructor could possibly consider so secret. And he wanted to know right now. Perhaps the new knowledge would make him the best fighter In Hong Kong. He knew he would like that. It would win him the admiration and friendship of virtually every teenager in the Crown Colony. But at the same time, he also knew that he would never betray the old man's confidence. No matter what, he would keep his vow. However as the weeks unfolded, Yip Man made no effort to teach the boy anything new. Ah Hing began to wonder if perhaps he had dreamed the whole vow ceremony. Worse. Perhaps he had somehow offended his master and was no longer considered worthy. Still, he would not dare ask the old man about it. The knowledge did belong to him, after all. Then came another unexpected incident. At about three o'clock one morning, Ah Hing was awakened by the urgent tone of Yip Man's voice. "Ah Hing! Ah Hing!" he called, shaking the boy's shoulder. "Come. Come. Come," motioning toward the main workout room with his hand. Ah Hing thought that the school must be on fire, or that some similar tragedy was about to strike. He raced out of bed and followed his teacher, an attack dog ready for action. But once inside the workout room, Yip Man turned to him and commanded, "Now Ah Hing, show me the first form in wing chun. Show me your sil lum tao." The sil lum tao, or "way of the small idea," is one of wing chun's three major choreographed shadowboxing routines. These forms are designed to develop and maintain precise technique. The first contains the core of the wing chun system, although it focuses primarily on breathing, balance, coordination and concentration. A practitioner learns to move each arm independently and develop some sense of the full scope of the fighting art, which is how the form got its name, "small idea." Ah Hing began the form as Yip had demanded, striving for perfection. But each time he started to move, Yip Man would stop him. "No, no," he would insist. "Like this!" Then the old master would perform the same movement himself. At first Ah Hing could not see much difference between his own movement and that of the grandmaster. Yet he did not ask any questions. He knew that Yip Man did not like to explain. He preferred to teach by showing. Ah Hing began again. This time he noticed that Yip Man seemed to be upset with his basic stance. Oh, he thought, Yip no longer wants my feet to be pidgeon-toed in the horse stance. But parallel? Yes. Yip Man wants my feet parallel. Hey, that's not the way he teaches that stance in class! The boy looked up and Yip Man winked at him. The old fox was definitely up to something. Apparently he was putting over some kind of impish trick on his students. That must be what all that "vow" business was about. Well, Yip always did have a good sense of humor. Ah Hing resumed his efforts, slowly, moving on to the form's hand techniques. Yip tinkered with each one like a sculptor with clay, sometimes modifying and reshaping slightly, sometimes replacing or expanding. About a quarter of the way through the routine, Yip Man stopped, suddenly waved the boy off. "Go back to bed," he barked. "This is too advanced for you." Several more weeks passed. Yip never once mentioned the early morning lessons. And Ah Hing knew better than to ask. The old man may have changed his mind. He always preferred students who could learn fast, after being shown a movement only once or twice. Ah Hing had always been among the fastest, but evidently even he was not fast enough when it came to this other version of the sil lum tao. Then it happened again Yip Man aroused Ah Hing out of a sound sleep and dragged him, yawning profusely, into the workout room. The old master was well pleased with his young disciple. He had tested the boy twice to see if his teenage enthusiasm would get the better of him, to see if he would forget his vow and tell his friends. But to the contrary, Ah Hing had remained completely humble, honoring his word both after the vow ceremony and after the first secret lesson. From now on, and for as long as the boy lived with him, these private sessions could take place on a regular basis. "Tonight, my big husky boy," Yip told Ah Hing, smiling from ear to ear, "I am going to teach you to fight like a woman." Yip explained that the wing chun he taught in his school was the form of the art that he had learned from his first master, Chan Wah Shun. Chan had been a giant among the men of his day, standing well over six feet in height. He was quite strong and quite heavy.

"The wing chun that Yip taught him in private was the form of the art the old man had learned from his second master, Leung Bik."

But wing chun was a woman's fighting art, founded by the Shaolin nun Ng Mui-with a woman's physical limitations in mind. The art therefore stressed mobility and evasion in opposition to brute force, deceptive yet easily controlled closes and withdrawals, and an assortment of quick cheap-shot surprises such as finger pokes and elbow strikes. However for Chan Wah Shun, due to his great size, such tactics were both awkward and unnecessary. His physical bulk permitted him to charge straight at an opponent, like an angry rhino, thundering through all counterattacks. He could then trap his opponent's arms and club him to submission with a succession of rapid punches from his massive fists. Thus under Chan, a system of feminine evasions was changed nearly beyond recognition. An imaginary straight line, called the "centerline," was drawn from the solar plexus to the opponent's chin. And as long as the centerline remained in proper alignment, directly in front of an opponent, a Chan Wah Shun student could attack in a straight line, with straight punches, straight up the opponent's middle. The clenched fist became the primary offensive weapon, reinforced by secondary open-hand work and low kicks. In contrast, Ah Hing discovered, the wing chun that Yip taught him in private was the form of the art the old man had learned from his second master, Leung Bik. Leung had been a short man, like Yip himself, standing about five feet tall. He, therefore, stressed the feminine elements of the art. Leung Bik divided wing chun combat into four theoretical phases which dictated how a womanor any slightly built person -could safely close, control, strike, and retreat from more powerful foes. The first phase is the non-contact stage. Here, the wing chun woman stands well out of reach of her attacker's kicks, punches, and grabs. And instead of assuming Chan Wah Shun's stationary cat stance, she will face her enemy square on in a horse stance, feet parallel. Occasionally, adjusting to her enemy's movements, she will pivot or step to her right or left into a sideways-facing front stance. But at a all times she will keep her weight evenly distributed over both feet so that, like a tennis player receiving a serve, she will remain quick and mobile, changing directions easily from one side to the other. Also, she will keep her guard arms constantly aimed at her opponent, rotating them slightly if necessary. The shortest distance between two points is a straight line. And by focusing her arms on their eventual target, she guarantees that her opponent's initial kick or punch will not follow that straight course, but rather must take a wider or more circular path. Meanwhile she remains in position to take advantage of any momentary lapse in his defense. Lastly, she will perpetually monitor her opponent's elbows and knees to determine the real intentions of his techniques. If he assumes a fighting stance with one side forward, she will only have to watch his lead knee and elbow. She knows that because of his forward leg he will be unable to react quickly on one side. He will become vulnerable to attacks which exploit this weakness. In the second phase of combat, or the initial contact stage, the wing chun woman will have used her mobile evasiveness from the non-contact stage to pick the safest moment to close in on her opponent. When the time arrives, she might avoid a kick by interrupting the direction of her movements, quickly sidestepping before blocking. Or perhaps she will stop a punch immediately with an appropriate parry. But once contact has been made with her opponent, she must concern herself with controlling her "centralline," an imaginary straight line drawn from her solar plexus to the point of contact. She will not attempt to preserve frontal opposition with her opponent as recommended by Chan Wah Shun, but rather will use her footwork, pivoting and sidestepping, so that her body becomes obliquely angled against her opponent's attack. Further, in order to prepare for the next phase of combat, she must use her contact reflexes to sense intuitively her opponent's next movement. The third phase of wing chun combat is the exchange stage, where the wing chun woman will unleash her own attacks. She will use her instinctive knowledge of the opponent's next movement, combined with trapping and maneuvering abilities, to keep her opponent's attacks neutralized as she moves closer. Then she will actually take control of an arm, especially at the elbow, so that she may secure a strategic position on her opponent's flank. Her attack will take the form of rapid finger, palm and elbow strikes supported by an occasional low kick or straight punch. She will constantly adjust to her opponent's movements, simultaneously neutralizing and striking. Her finger strikes will attack the ribs, chest, throat, eyes, and dim mak points. Her palm and elbow strikes will attack the more general head and body targets. And her closed fist will be used on only rare occasions. Ah Hing discovered that wing chun's third form, bil gee (thrusting fingers), taught the finger strikes. But the trapping, controlling, dim mak, and basic fighting techniques were found only in the wooden dummy. The final phase of wing chun combat is the withdrawal stage. Since the wing chun fighter expects to fight a larger opponent, he or she will sometimes need to use the side horse stance to flee quickly out of range. Then, once back at the non-contact stage, the four-phase process begins anew. During the three years that Ah Hing lived in Yip Man's home, he was exposed constantly to both the "centerline" wing chun of Chan Wah Shun and the "centralline" wing chun of Leung Bik. He knew that the difference between the two was essentially one of theoretical approach. Yet both versions of the art were as much a part of wing chun as the bobbingand-weaving style of Joe Frazier and the stick-and-move style of Mohammad Ali were a part of Western boxing. About a year-and-a-half after Ah Hing returned to his family, his parents arranged for him to go to school in Australia. He was then 18 years old. But for the sake of convenience, once in Australia he westernized his given name of Cheung Cheuk Hing. The

name he chose was William Cheung. Black Belt Magazine (Part IV of a series of four articles), 1983

|