|

by Eric Oram (extracted from Martial Arts Combat Sports magazine ) Looking back to my early karate days, I clearly remember the frustration I experienced during sparring. No matter how I tried to apply the multitude of techniques I thought I knew, somehow I always felt like a dog chasing his own tail at the end of the day. In spite of all the trophies, encouragement and praise, the truth of the matter was all of my "skill" disappeared when the situation became random. Why? I realize now that my reflexes had not been properly trained. My subconscious mind had not been given a clear and effective road map to follow when engaging a live opponent. All of my understanding was just that: understanding an intellectual and conceptual exercise, not a visceral understanding with the conscious mind free of thought, allowing the "moment" to take over. My reflexes were never free to roam. They were consistently held captive while I tried to understand the situation, then I would react to it. And it was always too late ... pow! Got hit again ... pow! That side kick ... If you don't know where you're going, you don't know when you're there. Even if the destination is known, you must still have an accurate map to show the way. And not just any route ... as the crow flies. Science Lesson In the October issue of Martial Arts & Combat Sports, I discussed

the science behind the blocking system of traditional wing * Guard your centerline. The shortest distance between two points is a

straight line. Guard the quick path; force your opponent to take a longer

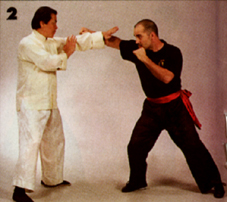

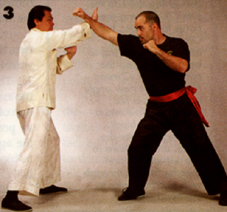

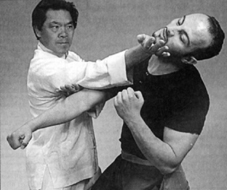

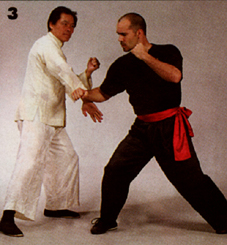

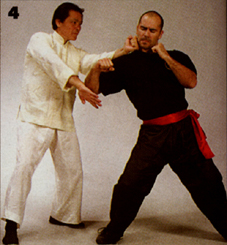

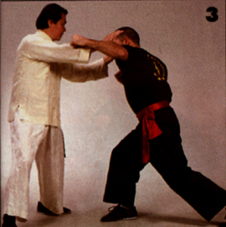

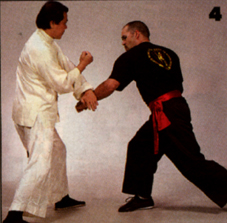

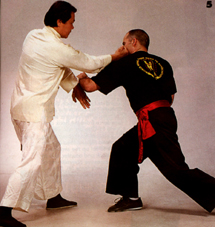

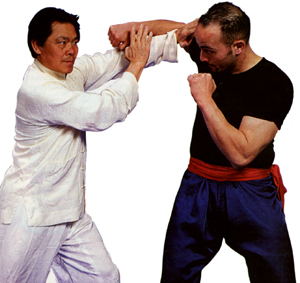

(circular) path. The focus of these principles is to guide the practitioner from the pre-contact stage to contact - establishing the map to assessing an attack and preparing the proper defense against it. Now that we are there - at contact - having successfully deflected the attack ... what is the next step? What is the absolute priority at this next instant? All About Chi Sao There is an entire training system within the wing chun system that is called chi sao, which is also known as "sticky hands." It is dedicated to developing sensitivity and reflexes at the point of contact. With relaxed, fluid movement, the William Cheung (TWC) practitioner should launch from the point of touch like a loaded spring. This forward energy is then loaded into the blocks and the strikes of the system. It's important to allow the reflexes to flow easily and instantaneously from the moment of contact into the counterattack, using the opponent's own force to determine the opening. The objective is to shorten the response time of the reaction and the speed and economy of the movement. But speed is only the rate of motion. The reflexes are still in need of a guide from the point of contact. Through the chi sao, the practitioner's energy is properly prepared for the map we are about to follow.

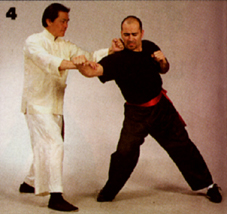

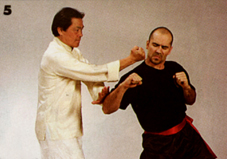

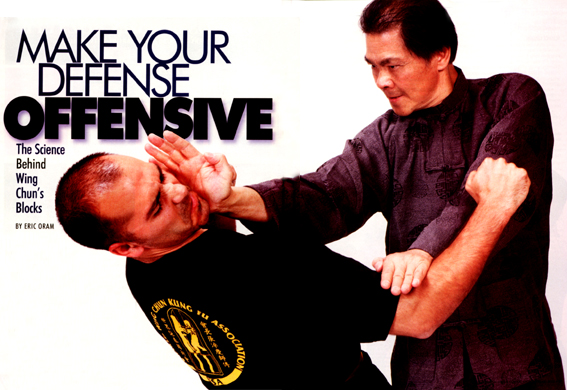

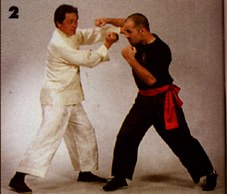

Can't Win on the Defensive Throughout the years of training with Grandmaster Cheung, I've heard him say a thousand times, "You can't win on the defensive!" How true it is. If you block two, they'll get you with No. 3. If you block 10, they get you with 11. That is why we must put the energy back into the direction of the opponent as quickly as possible - get him off of the agenda of attack and over to blocking and defense. This will change the dynamics of the encounter entirely. While the blocking arm reads the opponent's force, the other arm immediately counterattacks. Therefore, it is also imperative we have command over both arms at the same time - not just one after another. Thus, the most important ingredient, which also makes the TWC blocking system complete, is the overall position of the block. This should position you for your counterattack. There are two lines, or leverage systems, that are set up to operate simultaneously. The line of the block and the line of the counterattack. Therefore it is also imperative we have command over both arms at the same time - not just one after another. Thus, the most important ingredient, which also makes the TWC blocking system complete, is the overall position of the block. This should position you for your counterattack. There are two lines, or leverage systems, that are set up to operate simultaneously. The line of the block and the line of the counterattack. Therefore, each single position should provide leverage, the proper angle and the correct distance for each line. To achieve only one or the other leaves the situation incomplete. If you engage the opponent - at the moment of contact - strictly on defense, then what's to prevent the opponent from striking you again? You have blocked the strike, but the next moment is free to either your next attack or theirs. We need to eliminate the "or theirs" from that equation. If we do not, we can only pray that we are faster and more powerful than the opponent (a contest of force, not timing and strategy). What, then, is the key to the positioning? That nasty old nuisance: footwork.

Back to Basics The two key ingredients for the footwork in the TWC system are balance and mobility. We need a stable base to support our blocks, launch our attacks and absorb the opponent's force to a degree. And we want a free, neutral base to move the block and striking team to any location at any time. This mobility requires a balanced, 50/50 stance. The balance cannot afford to linger on one side or the other or it will lose the opportunity to follow any sudden changes in the distance and / or angle we are after. It is rather like a tennis player waiting for the serve - neutral and free to follow the ball according to the direction and angle of the ball's commitment. (This is not to say that wing chun is strictly defensive in nature, having to wait for the opponent to attack first before responding. There are certainly measures for bridging the gap offensively, but our context here is the defensive scenario.) At the same time, we must maintain a centered, balanced stance to provide the leverage and the correct distance for the block and counter. If we can't reach the target, we have no follow through and therefore no power. If we are too close, we will be too cramped to extend through the push of our attack. Understanding the footwork, therefore, is a crucial ingredient in executing the block and counter system as intended in the TWC system. The Roots

So, the keys to setting up the correct position are: * The defensive system discussed in the aforementioned interview. * The Next Threat Putting all of the elements together now, the final map looks like this: 1. Pre-Contact * Protect our centerline. 2. At Contact * Don't fight force with force.

Ultimate Objective In the end, we essentially engage our entire bodies in this reflex / response process, which is, again, the ultimate objective. Engrain this map deeply into the subconscious mind through thousands of hours of repetition and follow a precise map with simple, effective, scientific movement. If your movement follows this guide and addresses each of its elements, you will make it virtually impossible for the opponent to stay on the offensive. To do so, would be putting himself at great risk of getting hit. My objective here is to share what works for me and why, in hopes that it may spare the reader the same frustrations I experienced early on in my martial arts practice. Understanding the principles involved is a relatively simple task, once they are laid out. Like Occum's Razor tells us, the simplest solution is usually the best. Getting it into the reflexes, however, is another matter. That is the exclusive job of the practitioner and it requires repetition. For this, the only thing left to do is simply get back to practice.

[Index] |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

chun kung fu, as taught by Grandmaster William (Cheuk Hing)

Cheung. Without recounting the entire conversation, following is a list of the

principles that were discussed.

chun kung fu, as taught by Grandmaster William (Cheuk Hing)

Cheung. Without recounting the entire conversation, following is a list of the

principles that were discussed.

The Chinese have a saying, "Before there was the flower,

there was the root."

The Chinese have a saying, "Before there was the flower,

there was the root."